Hero Moments - North Stars for Your Outline

You have an idea for a story but can't figure out how to get it onto the page in a satisfying way. Let's see if we can't fix that.

Over the years, I’ve tried outlining in a variety of different ways: from highly detailed, might-as-well-be-a-rough-draft outlines, to bare bones, this-doesn’t-help-me-at-all outlines. I’ve tried drafting without an outline at all, and I’ve tried to follow someone else’s outlining process to varied results.

I’ve read dozens of books, watched and attended hundreds of hours of lectures, taken way too many classes, and all of which have taught me many valuable insights, but nothing that helps me create an outline that is as helpful as I want it to be.

So, I’ve decided to set out and make my own. Experiment with different ideas, try them out in practice through short stories and novel chapters, and refine them as I move forward. And as I push through and develop my writing process, I want to share my knowledge and exercises with you so you can learn and grow alongside me.

I’ll start by sharing what I currently do, its pros and cons, then share my revised process centered around Major Visual Actions, Emotion Elliciting Moments, and Promise, Progress, Payoff. Finally, I’ll share how I plan to implement this process in my next short story in an exercise you can follow along with.

So, let’s get started.

What I Do Now

My current process

My current outlining process follows closely with the process outlined in Outline Your Novel by Scott King, mixed with mapping my points out to a 3 act structure that looks like this:

Act 1:

Hook

Inciting Incident

End of Act 1 Hook

Act 2:

Develop and Complicate 1

Mid-Point Twist

Develop and Complicate 2

End of Act 2 Hook

Act 3:

Events leading to the climax

Climax

Denouement

I take Scott King’s approach of developing an idea, which goes from a single, refined sentence, to a 5-6 paragraph long summary of the entire idea, then map those paragraphs onto the structure above to find where I’m lacking and what needs to be improved.

I then break each of these elements into chapters and scenes. There’s not really a process behind this. Usually a point of view shift or time skip will mark the end of a chapter, and the end of a scene is whenever I would move the focal point of the action (move the “camera” as it were).

Usually I get 3-4 scenes per chapter, with some outliers being as few as 1 scene and as many as 6, and that feels pretty good.

However, Scott King’s approach for outlining scenes, to me, doesn’t give me a good enough direction. The structure for each scene looks like this:

Scene 1 —

POV —

Synopsis —

Location —

Story Beat —

Character Beat —

Opening —

POV Immediate Want —

POV Long Want —

Internal Conflict —

External Conflict —

Reader Reaction —

Ending —

I find that the “Opening” and “Ending” sections are good, as well as identifying the POV character’s immediate want and long want, but the location, synopsis, conflict types, and reader reactions don’t do much to guide me when writing a scene.

I’d rather figure out that stuff while writing, and have a stronger roadmap for what’s going on in the middle of a scene.

Pros and Cons

Pros — I can take an idea and flesh it out enough to get a full story out of it. I can identify pacing problems early and adjust before writing out a rough draft. I can break moments down into chapters and scenes. I know where each scene starts and ends.

Cons — There’s a lot of information that doesn’t necessarily change from scene to scene that requires being filled out. There isn’t anything directing pacing within a given scene or chapter. There isn’t enough direction when in the middle of a scene. There’s too much specificity in things like Reader Reactions. Internal/External Conflict fields feel irrelevant/less important than they should be.

New Ingredients

Okay, now that we’ve seen what I currently do, I need to figure out what I plan to modify this with. I’ll be relying on three major ideas, which I’ll outline below before creating a new outlining process using those ideas.

1. Major Visual Actions

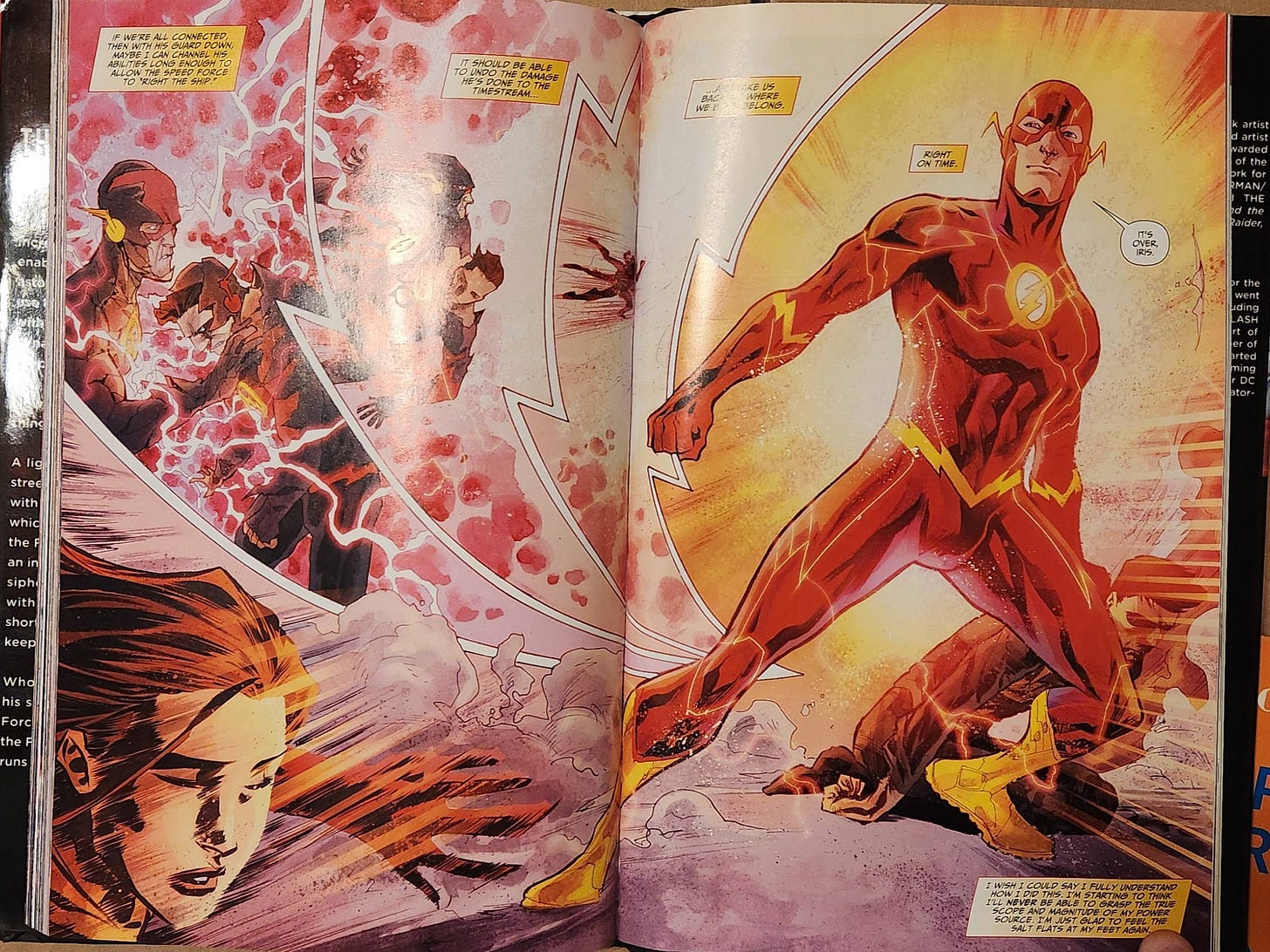

I learned this while reading The DC Comics Guide to Writing Comics by Dennis O’Neil. Essentially, comic books have single page spreads and double page spreads that take place at specific points. These are single pieces of artwork that take up the entire page, or two pages, and serve as focal points for the story. They need to be highly visual, usually taking place at points of climactic action in the story, and commonly happen at the End of Act 1, the Middle of Act 2 (double page spread being the center of the comic book, where the staples are and where the book would naturally open up to) and at the very End of Act 3, either after the Climax or Denouement (resolution).

I’ve already been relying on Major Visual Actions as my capstones for the End of Act 1, the Mid-Point Twist, and an optional one after the Climax. However, it feels limiting to look at a whole story and only identify the 2-3 moments of high visual action, especially in books where you’re writing stories much longer than comics, which are typically only 24-32 pages(ish. Plenty of comics break this rule, especially today).

These are great moments: the points in the story that stick in the reader’s mind, ideally long after the story is finished. They’re eye-catching. They’re the moments that, when you’re asked to describe a book to someone, you’re going to mention. These are also very PLOT centric.

2. Emotion Eliciting Moments

This is not a principle I have learned from any given book or lecture, but rather something I’ve noticed I gravitate toward while reading. These are moments in the story that elicit strong emotion from me as a reader. Moments that make me cry, or shout, or jump for joy, etc. Often these are CHARACTER focused, and they sometimes coincide with Major Visual Actions for me personally in terms of what I tell people about when they ask me about a book I like. However, just because they often coincide with Major Visual Actions, does not mean they are the same thing.

To use Star Wars as an example:

Major Visual Action — The Death Star exploding, signaling the end of the Empire and the victory of the Rebels.

Emotion Eliciting Moment — Luke choosing to turn off his targeting system and trust in the force to launch his torpedoes.

These two moments coincide, and one even leads directly into the other, but I get the most emotional fulfillment out of seeing those torpedoes go into the exhaust vent than I do at seeing the spectacle of the Death Star exploding. I believe this has something to do with how you relate to characters more than plot because they’re the human element of a story, and I think these can take place separately from Major Visual Actions, but are often strongest when they are placed together, especially toward the climax of the story.

3. Promise, Progress, and Payoff

A tool taken from Brandon Sanderson’s Writing Lectures on YouTube. He does a fantastic job explaining this concept himself, but I’ll give a rough overview here. Essentially, every book is a series of Promises made to the reader, Progression toward fulfilling those promises, and Payoffs to those promises. To use Star Wars as an example again:

Promise — Luke wants to explore the galaxy and be a hero.

Progress — Luke meets Obi-Wan, Han Solo, rescues Leia from the Death Star, unites with the Rebels, and launches an assault against the Death Star.

Payoff — The Death Star explodes and the Rebels win.

This is, essentially, a 3-act structure. What I like the most about it, though, is that it is fractal. It can be used to identify an entire book, all the way down to a single scene, or even more minutely than that, such as a single exchange of dialogue or action. It can also be applied to PLOT and CHARACTER, with different and overlapping promises, progress, and payoffs for each.

Hero Moments

Hero Moments work like this: identify points in the story you’re leading into early that are highly visual and/or elicit emotion, then utilize Progress, Promise, and Payoff to build up to those moments in a satisfying way. Map these moments out onto a 3 act (or preferred) structure to ensure pacing, continuity, and rising action, and start chaining them together in a satisfying way to keep readers engaged and ensuring you are always leading up to a big payoff that will stick with readers afterward.

Hero Moments will essentially replace the “Payoff” step in Sanderson’s Promises, Progress, and Payoff, while aiming to ensure they are both highly visual, highly emotional, or both.

Now, “highly visual” in this case doesn’t necessarily mean something blowing up. What it does mean is that there’s action associated with the character moment, so we don’t reach a moment of high emotion (internal fulfillment) without any action (external fulfillment), or vice versa.

In my mind, it makes sense to split these into Major and Minor Hero Moments, so I’ll do that and define what each of them mean before moving onto the outline.

Major Hero Moment — moments in the wide arching plot that push, twist, or set back the story. These are things like the End of Act 1, the big Mid-Point twist, or the Major Visual Action in the Climax.

Minor Hero Moment — the minor steps that cap off a chapter that serve as the Promise and Progress toward the Major Hero Moments you’re building up to.

Outline and Exercise

Here’s how I plan to create my next story outline using Hero Moments:

Brainstorm and Identify — Discover the moments in your story that motivate you to write it. Big emotional moments, crazy fight scenes, climaxes, twists, hooks, etc. Things you cannot wait to write or for readers to read.

Map Out and Pace — Using the 3 act (or preferred) structure, lay out the Major Hero Moments to make sure they are appropriately paced and ramp up the tension/satisfy the reader.

Identify Minor Hero Moments — Outline what events MUST take place from beginning to end that would build up to the Major Hero Moments. Make these as visual/emotional as you can and set these as Minor Hero Moments.

NOTE: Your Major Hero Moments should serve as the Minor Hero Moments building up to your Climax. These Major Moments are the promise and progress of your whole story.

Separate and Weave — Separate Minor Hero Moments into chapters, with the Hero Moment capping off a chapter, and figure out which promises and progresses should be weaved together (IE: the progress toward the End of Act 1 Hero Moment can also serve as the initial promise of the Mid-Point Twist Hero Moment. Identify where those overlaps can take place and merge them together to work toward multiple things at once).

Chapter Promises and Progression — Using the Minor Hero Moments at the end of your chapters as a guide, outline the chapter using promises and progressions toward that eventual payoff that will be both highly visual and highly emotional. These serve as your scenes. This ensures each chapter is focused and ends in a satisfying way.

Denouement and New Promises — Ensure that each resolution ends with either a new promise or progress toward another Hero Moment. This can look like cliffhangers, but also like minor steps forward and backward, and serve to motivate the reader to continue reading until the very end where the final Denouement caps off the entire story (with potential leads into the next story if there’s a sequel planned).

I know this might be confusing without an example, and I will update this post with one once I write a chapter/story using this method. This is also my first time writing this method down and explaining it. As I use and refine this method, the way I speak about it will also be refined until it’s more like an actual lesson of “here’s how I do things” rather than a first attempt and communicating an idea, as it is now.

Example

NOTE: I will come back and edit this once I write a story or chapter using this new method.